---

title: "Coupling"

format:

html:

code-fold: false

toc: true

toc-depth: 3

fig-width: 8

out-width: "100%"

jupyter: python3

execute:

cache: true

---

# Introduction

Coupling defines how network nodes interact through structural connectivity. While dynamics govern local temporal evolution at each node, coupling transmits information between nodes, enabling collective behaviors like synchronization, wave propagation, and functional integration.

The general form of coupling input is:

$$

c_i = \sum_{j} w_{ij} \cdot f(\text{state}_j, \text{state}_i, \theta)

$$

where $w_{ij}$ represents connection weights from the graph, and $f$ is the coupling function with parameters $\theta$.

# Coupling in Network Dynamics

Coupling integrates with dynamics through named input channels. The `dynamics()` method receives coupling as a `Bunch` object with named attributes:

```python

def dynamics(self, t, state, params, coupling, external):

# Access coupling inputs by name

c_instant = coupling.instant[0]

c_delayed = coupling.delayed[0]

# Use in dynamics equations

dX_dt = ... + c_instant + c_delayed

return derivatives

```

Networks support multiple coupling types through a named dictionary:

```{python}

import jax.numpy as jnp

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics import Network, solve

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.dynamics import ReducedWongWang

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling import LinearCoupling

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.graph import DenseGraph

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.solvers import Euler

# Create simple network

dynamics = ReducedWongWang()

graph = DenseGraph(jnp.array([[0.0, 1.0], [1.0, 0.0]]))

coupling = LinearCoupling(incoming_states='S', G=0.5)

network = Network(

dynamics=dynamics,

coupling={'instant': coupling}, # Named coupling

graph=graph

)

print(network)

```

**Key point**: If a dynamics model declares coupling inputs that are not provided in the network, those inputs are automatically filled with zeros. This allows flexible network configurations without requiring all possible couplings.

# The Coupling API

Coupling objects follow a three-phase lifecycle that mirrors the simulation flow:

## Phase 1: Preparation (*prepare*)

Called once before simulation starts:

```python

coupling_data, coupling_state = coupling.prepare(network, dt)

```

**Returns**:

- `coupling_data` (Bunch): Static precomputed data

- State indices to extract from network state

- Delay step indices (for delayed coupling)

- Optimization flags (sparse/dense modes)

- `coupling_state` (Bunch): Mutable internal state

- History buffers (for delayed coupling)

- Empty for instantaneous coupling

## Phase 2: Computation (*compute*)

Called every time step during integration:

```python

coupling_input = coupling.compute(t, state, coupling_data,

coupling_state, params, graph)

```

**Returns**:

- Coupling input array `[n_coupling_dims, n_nodes]`

## Phase 3: State Update (*update_state*)

Called after each integration step:

```python

coupling_state = coupling.update_state(coupling_data,

coupling_state, new_state)

```

**Returns**:

- Updated `coupling_state` (e.g., updated history buffer)

**Flow pseudocode**:

```python

# Before simulation

coupling_data, coupling_state = coupling.prepare(network, dt)

# During simulation (at each time step)

for step in range(n_steps):

# Compute coupling input

coupling_input = coupling.compute(t, state, coupling_data,

coupling_state, params, graph)

# Integrate dynamics (uses coupling_input)

new_state = integrate_step(state, coupling_input, dt)

# Update coupling state

coupling_state = coupling.update_state(coupling_data,

coupling_state, new_state)

state = new_state

```

# TVB-Style Couplings: Pre and Post Pattern

Most brain network models follow a standard coupling pattern: transform states before aggregation (`pre`), perform weighted summation, then transform the result (`post`). This pattern is captured in the `InstantaneousCoupling` and `DelayedCoupling` base classes.

The computation flow is:

```

pre(states) → weighted sum → post(sum)

```

## LinearCoupling Example

The simplest coupling applies a gain and offset to the weighted sum:

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling import LinearCoupling

# Create linear coupling

coupling = LinearCoupling(incoming_states='x', G=2.0, b=0.1)

print(f"Coupling parameters: G={coupling.params.G}, b={coupling.params.b}")

print(f"Incoming states: {coupling.INCOMING_STATE_NAMES}")

```

The `post()` implementation is simple:

```python

def post(self, summed_inputs, local_states, params):

return params.G * summed_inputs + params.b

```

Since `pre()` is not overridden, it returns incoming states unchanged (identity function).

## DifferenceCoupling: Overriding Pre

When coupling depends on differences between nodes, we override `pre()`:

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling import DifferenceCoupling

# Difference coupling: couples based on (x_j - x_i)

diff_coupling = DifferenceCoupling(

incoming_states='x',

local_states='x', # Need local state for difference

G=1.0

)

print(f"Incoming states: {diff_coupling.INCOMING_STATE_NAMES}")

print(f"Local states: {diff_coupling.LOCAL_STATE_NAMES}")

```

The `pre()` method computes differences:

```python

def pre(self, incoming_states, local_states, params):

# incoming_states: [n_states, n_nodes, n_nodes] per-edge format

# local_states: [n_states, n_nodes]

return incoming_states - local_states[:, :, None]

```

This enables synchronization dynamics where coupling strength depends on state mismatch.

# Vectorized vs Per-Edge Modes

A key performance consideration is how coupling interacts with the connectivity matrix. TVB-Optim supports two modes:

**Per-Edge Mode (3D)**: `pre()` returns `[n_states, n_nodes, n_nodes]`

- Element-wise multiply with weights: `pre_states * weights`

- Then sum over source nodes

- Flexible: supports per-connection transformations

- Slower for dense graphs

**Vectorized Mode (2D)**: `pre()` returns `[n_states, n_nodes]`

- Matrix multiplication: `pre_states @ weights`

- Faster for dense graphs (optimized BLAS)

- Less flexible: same operation for all connections

## LinearCoupling vs FastLinearCoupling

`FastLinearCoupling` achieves vectorized mode by using `local_states` instead of `incoming_states`:

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling import FastLinearCoupling

# Standard: uses incoming_states (per-edge)

standard = LinearCoupling(incoming_states='S', G=1.0)

# Fast: uses local_states (vectorized)

fast = FastLinearCoupling(local_states='S', G=1.0)

print("Standard coupling mode: per-edge (3D)")

print("Fast coupling mode: vectorized (2D)")

```

The difference is in `pre()`:

```python

# LinearCoupling: inherits default pre() returning incoming_states (3D)

# → per-edge mode

# FastLinearCoupling:

def pre(self, incoming_states, local_states, params):

return local_states # 2D → vectorized mode

```

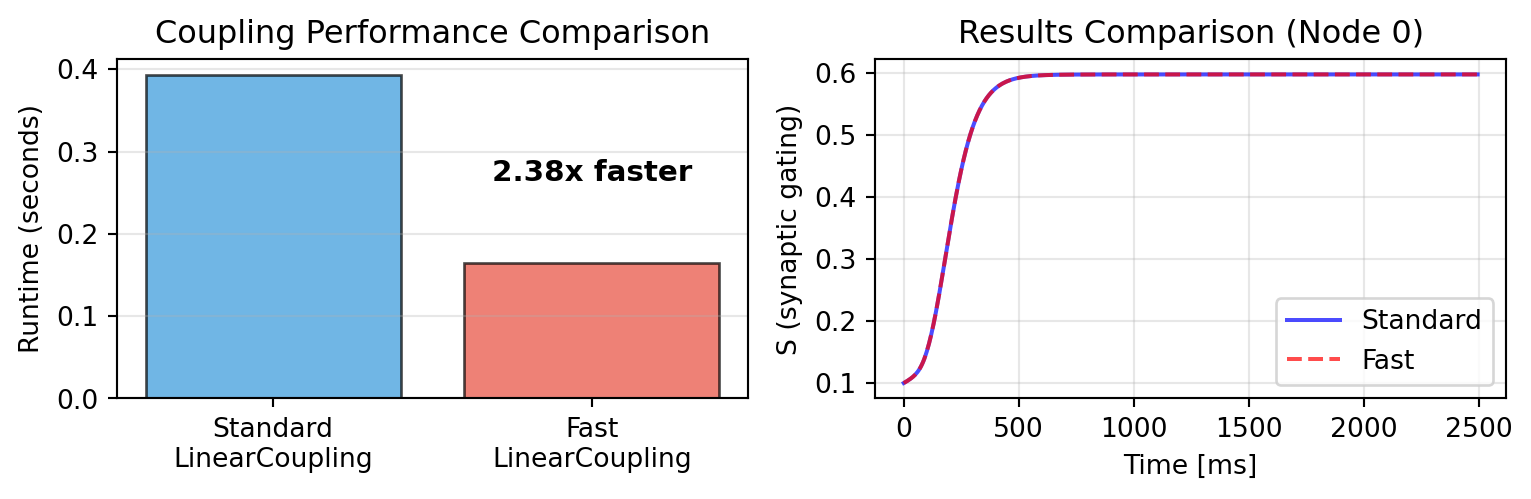

## Performance Benchmark

Let's compare runtime with empirical connectivity (84 regions, 5000 time steps):

```{python}

import time

from tvboptim.data import load_structural_connectivity

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.dynamics.tvb import ReducedWongWang

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.solvers import Heun

# Load empirical connectivity

weights, lengths, labels = load_structural_connectivity("dk_average")

weights_norm = weights / jnp.max(weights) # Normalize

print(f"Network size: {weights.shape[0]} nodes")

print(f"Simulation: 5000 steps (dt=0.5 ms)")

# Setup

dynamics = ReducedWongWang()

graph = DenseGraph(weights_norm)

# Standard LinearCoupling (per-edge mode)

coupling_standard = LinearCoupling(incoming_states='S', G=0.5)

network_standard = Network(dynamics=dynamics, coupling={'instant': coupling_standard}, graph=graph)

# FastLinearCoupling (vectorized mode)

coupling_fast = FastLinearCoupling(local_states='S', G=0.5)

network_fast = Network(dynamics=dynamics, coupling={'instant': coupling_fast}, graph=graph)

solver = Heun()

n_steps = 5000

dt = 0.5

# Benchmark: Standard coupling

start = time.time()

result_standard = solve(network_standard, solver, t0=0.0, t1=n_steps*dt, dt=dt)

time_standard = time.time() - start

# Benchmark: Fast coupling

start = time.time()

result_fast = solve(network_fast, solver, t0=0.0, t1=n_steps*dt, dt=dt)

time_fast = time.time() - start

print(f"\nStandard LinearCoupling: {time_standard:.3f} s")

print(f"FastLinearCoupling: {time_fast:.3f} s")

print(f"Speedup: {time_standard/time_fast:.2f}x")

```

```{python}

#| code-fold: true

#| code-summary: "Visualization"

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(1, 2, figsize=(8.1, 2.7))

# Bar chart

couplings = ['Standard\nLinearCoupling', 'Fast\nLinearCoupling']

times = [time_standard, time_fast]

colors = ['#3498db', '#e74c3c']

ax1.bar(couplings, times, color=colors, alpha=0.7, edgecolor='black')

ax1.set_ylabel('Runtime (seconds)')

ax1.set_title('Coupling Performance Comparison')

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3, axis='y')

# Add speedup annotation

speedup = time_standard / time_fast

ax1.text(1, time_fast + 0.1, f'{speedup:.2f}x faster',

ha='center', fontsize=11, fontweight='bold')

# Verify results are similar

ax2.plot(result_standard.ts[::10], result_standard.ys[::10, 0, 0],

'b-', label='Standard', alpha=0.7)

ax2.plot(result_fast.ts[::10], result_fast.ys[::10, 0, 0],

'r--', label='Fast', alpha=0.7)

ax2.set_xlabel('Time [ms]')

ax2.set_ylabel('S (synaptic gating)')

ax2.set_title('Results Comparison (Node 0)')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

For dense networks, vectorized mode provides significant speedup while producing identical results. Use `FastLinearCoupling` when:

- Coupling function is simple (linear)

- Performance is critical

Use standard (per-edge mode) like `LinearCoupling` when:

- Need per-connection transformations

- Coupling is complex (differences, nonlinearities)

# Creating Custom Couplings: Adaptive Gain

Let's implement an adaptive coupling where coupling strength adjusts based on local activity - a homeostatic mechanism common in biological networks that allows nodes to maintain independent dynamics despite strong connectivity.

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.core.bunch import Bunch

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling.base import InstantaneousCoupling

class AdaptiveGainCoupling(InstantaneousCoupling):

"""Coupling with activity-dependent gain modulation.

Coupling strength decreases with local activity:

G_effective = G * (1 - alpha * |local_state|)

This implements homeostatic regulation where highly active

nodes reduce their coupling sensitivity.

"""

N_OUTPUT_STATES = 1

DEFAULT_PARAMS = Bunch(

G=1.0, # Base coupling strength

alpha=0.5 # Adaptation strength (0 = no adaptation)

)

def post(self, summed_inputs, local_states, params):

"""Apply activity-dependent gain modulation."""

# Measure local activity (amplitude of oscillations)

activity = jnp.abs(local_states[0])

# Effective gain decreases with activity

G_effective = params.G * (1.0 - params.alpha * activity)

return G_effective * summed_inputs

print("Adaptive coupling class defined!")

```

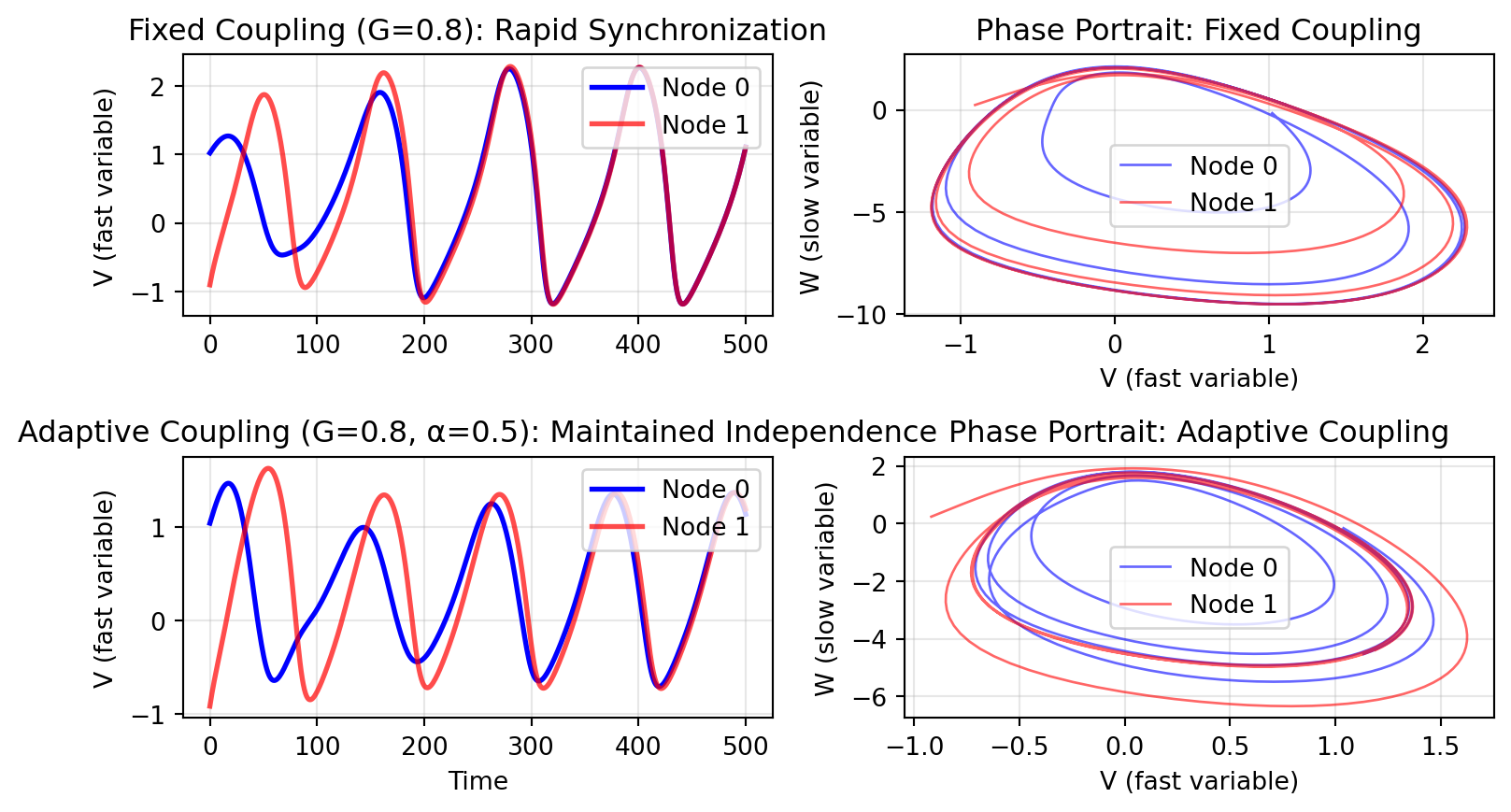

## Demonstrating Adaptive vs Fixed Coupling

We'll use two coupled oscillators with different initial conditions. Fixed coupling forces rapid synchronization, while adaptive coupling allows them to maintain more independent oscillations.

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.dynamics.tvb import Generic2dOscillator

# Bidirectional coupling between two nodes

graph_osc = DenseGraph(jnp.array([[0.0, 1.0], [1.0, 0.0]]))

# Create oscillatory dynamics with different initial conditions per node

dynamics_fixed = Generic2dOscillator(

a=2.0, # Parameter controlling oscillation frequency

b=-10.0, # Damping

c=0.0,

d=0.02,

tau=1.0,

I=0.0,

INITIAL_STATE=(1.0, 0.0) # Node 0 starts here

)

dynamics_adaptive = Generic2dOscillator(

a=2.0,

b=-10.0,

c=0.0,

d=0.02,

tau=1.0,

I=0.0,

INITIAL_STATE=(1.0, 0.0)

)

# Fixed coupling: strong constant gain

fixed_coupling = LinearCoupling(incoming_states='V', G=0.8)

network_fixed = Network(

dynamics=dynamics_fixed,

coupling={'instant': fixed_coupling},

graph=graph_osc

)

# Adaptive coupling: same base gain but adapts

adaptive_coupling = AdaptiveGainCoupling(

incoming_states='V',

local_states='V', # Need local state for adaptation

G=0.8,

alpha=0.9

)

network_adaptive = Network(

dynamics=dynamics_adaptive,

coupling={'instant': adaptive_coupling},

graph=graph_osc

)

# Manually set different initial conditions for second node

initial_state_fixed = network_fixed.initial_state.at[:, 1].set(jnp.array([-1.0, 0.0]))

initial_state_adaptive = network_adaptive.initial_state.at[:, 1].set(jnp.array([-1.0, 0.0]))

# Update network history to use custom initial states

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.result import NativeSolution

network_fixed.update_history(NativeSolution(ts=jnp.array([0.0]), ys=initial_state_fixed[None, :, :]))

network_adaptive.update_history(NativeSolution(ts=jnp.array([0.0]), ys=initial_state_adaptive[None, :, :]))

# Simulate both

result_fixed = solve(

network_fixed, Euler(),

t0=0.0, t1=500.0, dt=1.0

)

result_adaptive = solve(

network_adaptive, Euler(),

t0=0.0, t1=500.0, dt=1.0

)

print(f"Simulation complete: {len(result_fixed.ts)} time steps")

```

```{python}

#| code-fold: true

#| code-summary: "Visualization"

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 2, figsize=(8.1, 4.63))

# Time series - Fixed coupling

axes[0, 0].plot(result_fixed.ts, result_fixed.ys[:, 0, 0], 'b-', label='Node 0', linewidth=2)

axes[0, 0].plot(result_fixed.ts, result_fixed.ys[:, 0, 1], 'r-', label='Node 1', linewidth=2, alpha=0.7)

axes[0, 0].set_ylabel('V (fast variable)')

axes[0, 0].set_title('Fixed Coupling (G=0.8): Rapid Synchronization')

axes[0, 0].legend(loc='upper right')

axes[0, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# axes[0, 0].set_xlim(0, 100)

# Time series - Adaptive coupling

axes[1, 0].plot(result_adaptive.ts, result_adaptive.ys[:, 0, 0], 'b-', label='Node 0', linewidth=2)

axes[1, 0].plot(result_adaptive.ts, result_adaptive.ys[:, 0, 1], 'r-', label='Node 1', linewidth=2, alpha=0.7)

axes[1, 0].set_xlabel('Time')

axes[1, 0].set_ylabel('V (fast variable)')

axes[1, 0].set_title('Adaptive Coupling (G=0.8, α=0.5): Maintained Independence')

axes[1, 0].legend(loc='upper right')

axes[1, 0].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# axes[1, 0].set_xlim(0, 100)

# Phase portraits - Fixed coupling

axes[0, 1].plot(result_fixed.ys[:, 0, 0], result_fixed.ys[:, 1, 0],

'b-', linewidth=1, alpha=0.6, label='Node 0')

axes[0, 1].plot(result_fixed.ys[:, 0, 1], result_fixed.ys[:, 1, 1],

'r-', linewidth=1, alpha=0.6, label='Node 1')

axes[0, 1].set_xlabel('V (fast variable)')

axes[0, 1].set_ylabel('W (slow variable)')

axes[0, 1].set_title('Phase Portrait: Fixed Coupling')

axes[0, 1].legend()

axes[0, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Phase portraits - Adaptive coupling

axes[1, 1].plot(result_adaptive.ys[:, 0, 0], result_adaptive.ys[:, 1, 0],

'b-', linewidth=1, alpha=0.6, label='Node 0')

axes[1, 1].plot(result_adaptive.ys[:, 0, 1], result_adaptive.ys[:, 1, 1],

'r-', linewidth=1, alpha=0.6, label='Node 1')

axes[1, 1].set_xlabel('V (fast variable)')

axes[1, 1].set_ylabel('W (slow variable)')

axes[1, 1].set_title('Phase Portrait: Adaptive Coupling')

axes[1, 1].legend()

axes[1, 1].grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

```

The key difference:

- **Fixed coupling**: Nodes quickly synchronize and oscillate in phase (overlapping trajectories)

- **Adaptive coupling**: Nodes maintain more independent oscillations with persistent phase differences

When oscillation amplitude increases, adaptive coupling reduces its strength, preventing complete synchronization. This demonstrates how `local_states` in `post()` enables state-dependent coupling mechanisms that can maintain network diversity despite strong structural connectivity.

# Delays

Brain networks exhibit transmission delays due to finite axonal conduction speeds. The `DelayedCoupling` base class handles delayed interactions automatically.

## Delay Computation

Delays are computed from tract lengths and conduction speed:

$$

\tau_{ij} = \frac{\text{length}_{ij}}{\text{speed}}

$$

The default conduction speed is **3 m/s** (typical for unmyelinated axons). Tract lengths are stored in the graph's delay matrix.

## Implementation Details

Delayed coupling maintains a **history buffer** - a circular buffer storing past states. During `compute()`, the appropriate delayed states are extracted based on connection-specific delays.

**Computational cost**: Delayed coupling requires more memory access for indexing into the history buffer at different time offsets per connection. This is more expensive than instantaneous coupling but essential for biological realism.

## Example

```{python}

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.coupling import DelayedLinearCoupling

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.graph import DenseDelayGraph

from tvboptim.experimental.network_dynamics.dynamics import Lorenz

# Create graph with delays (convert tract lengths to delays at 3 m/s)

weights_small = jnp.array([[0.0, 1.0], [1.0, 0.0]])

lengths_small = jnp.array([[0.0, 30.0], [30.0, 0.0]]) # 30 mm tract length

delays_small = lengths_small / 3.0

graph_delayed = DenseDelayGraph(weights_small, delays_small)

# Delayed coupling

delayed_coupling = DelayedLinearCoupling(incoming_states='x', G=0.5)

# Create network

network_delayed = Network(

dynamics=Lorenz(),

coupling=delayed_coupling,

graph=graph_delayed

)

print(f"Tract length: {lengths_small[0, 1]} mm")

print(f"Conduction speed: 3 m/s (default)")

print(f"Delay: {lengths_small[0, 1] / 3:.1f} ms")

```

Delayed coupling requires `DelayGraph` (or `SparseDelayGraph`) which stores both weights and delays. See the [Graph](graph.qmd) section for details on delay graph construction.

# Multiple Couplings

Networks can have multiple coupling mechanisms simultaneously. Dynamics models declare which coupling inputs they expect via `COUPLING_INPUTS`:

```python

class MyDynamics(AbstractDynamics):

COUPLING_INPUTS = {

'instant': 1, # Expects 1D instantaneous coupling

'delayed': 1 # Expects 1D delayed coupling

}

def dynamics(self, t, state, params, coupling, external):

c_instant = coupling.instant[0]

c_delayed = coupling.delayed[0]

# Use both in dynamics

...

```

When creating a network, provide couplings as a named dictionary:

```python

network = Network(

dynamics=dynamics,

coupling={

'instant': LinearCoupling(incoming_states='S', G=1.0),

'delayed': DelayedLinearCoupling(incoming_states='S', G=0.5)

},

graph=graph # Must be DelayGraph for delayed coupling

)

```

**Key behavior**: If a dynamics model declares coupling inputs that are not provided, those inputs are **automatically filled with zeros**. This allows flexible configurations:

```python

# Model declares both instant and delayed, but only provide instant

network = Network(

dynamics=dynamics,

coupling={'instant': coupling_instant}, # 'delayed' will be zeros

graph=graph

)

```

This zero-filling enables gradual model building and testing without requiring all coupling types upfront.

# Summary

See the [API Reference](../reference/index.qmd) for complete parameter descriptions and available coupling types.

Coupling enables inter-region communication in brain networks:

- **Lifecycle**: Three-phase pattern (`prepare` → `compute` → `update_state`) mirrors simulation flow

- **TVB pattern**: Most couplings use `pre()` → weighted sum → `post()` pattern; typically only `post()` needs implementation

- **Performance**: Vectorized mode (2D) faster for dense graphs; per-edge mode (3D) more flexible

- **Delays**: Computed from tract lengths and conduction speed; managed automatically via history buffers with increased computational cost

- **Multiple couplings**: Named dictionary with automatic zero-filling for missing inputs

- **Custom couplings**: Subclass `InstantaneousCoupling` or `DelayedCoupling` and override `pre()`/`post()`

Coupling integrates with [Dynamics](dynamics.qmd) through named inputs and with [Graph](graph.qmd) through connectivity structure. Together they define collective network behavior.